Plastic pollution is a global problem, but local interventions are critical to address the challenge

-

-

Nurul Aisyah Suwandi

-

February 22, 2023

-

7 min read

Nurul Aisyah Suwandi

February 22, 2023

7 min read

With plastic waste leakage into the environment projected to double to 44 million tonnes annually by 2060, pressure has been building to find impactful solutions that address the entire lifecycle of plastic and advances the shift towards circularity. As we approach the second negotiations for an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, it is important that we take a step back to evaluate the priorities that must be considered. While it is essential that the agreement matches the global scale of the problem, we also need to recognize that the plastic supply chain varies considerably between countries.

A nuanced approach must sit alongside international cooperation and global actions. To do so, we need to build an accurate understanding of local plastic supply chains to ensure investment and efforts are directed to achieving the greatest impact and solutions are able to capitalize on the existing strengths of communities.

Closer to home in Asia, where 15 of the world’s 20 most polluted rivers are located, countries have taken steps to address plastic pollution, such as through the implementation of national action plans in Thailand, Indonesia, and Malaysia. However, a persistent gap remains. There is limited investigation into plastic supply chains in localized contexts and the unique characteristics of waste management in cities and municipalities, which are hotspots of plastic leakage.

Mapping local plastic recycling supply chains in selected cities

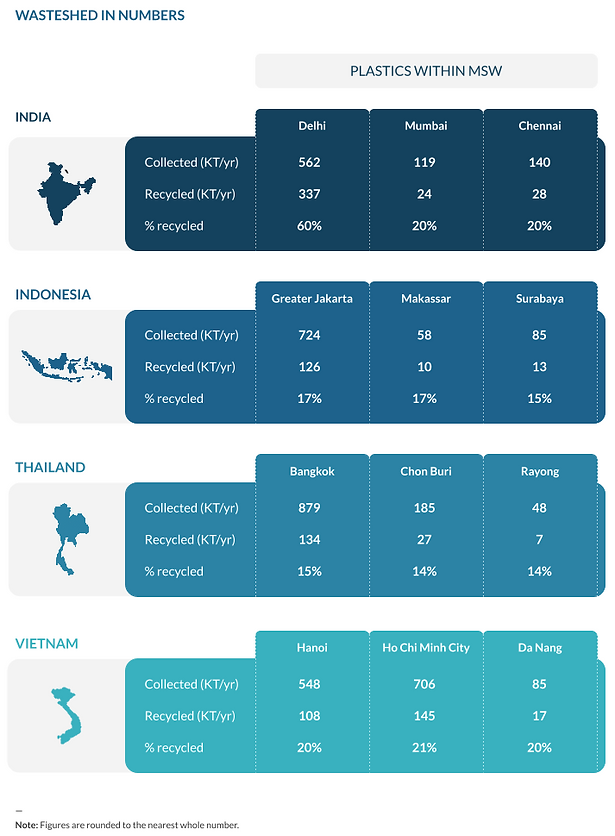

Recognizing this data gap, The Circulate Initiative, in partnership with Anthesis Group, embarked on a detailed assessment of 12 wastesheds1 across four countries in South and Southeast Asia. The resulting reports reveal distinct characteristics in waste management systems and practices and suggest improvements for local plastic recycling supply chains.

In nearly all wastesheds, 100% of the plastic waste that gets recycled is channeled through the informal sector

Informal waste workers across the 12 wastesheds are involved in a variety of processes, from collection to aggregation and in some cases, recycling of the plastic waste.

In Delhi, the informal workers, known as safai sathis, amount to 200,000 to 500,000, a significantly higher proportion compared to Mumbai and Chennai. The city’s higher recycling rate (60%) could be attributed to the wider coverage of these waste pickers and stronger demand from local recyclers, unlike in Chennai and Mumbai, where plastic waste is transported to states like Gujarat for recycling.

In some wastesheds, informal waste workers are leveraged for waste collection in areas that would have otherwise been inaccessible to the municipal waste trucks. For example, in Mumbai, informal collectors, supported by non-governmental organizations, collect material door-to-door and transport it to the communal bins provided in these areas. Although Ho Chi Minh City has explored the formalization of independent waste collectors through licensing, unintended trading and aggregation of collection permits by larger operators has forced the city to modify their strategy. Informal workers are now required to form legal entities such as cooperatives, which can participate in legal tenders and contracts.

Optimizing infrastructure that support recovery and recycling

Asia has seen significant advancements in plastic waste management infrastructure and services in recent years, as governments double down on efforts to reverse current trajectories of pollution. Indonesia, for example, developed infrastructure to support recycling through its unique waste bank system (bank sampah)2 and TPS3R (Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle) sites.3

However, the effects of these sites in raising plastic recycling rates remain to be seen. Greater Jakarta has over 3,000 waste banks, which manage only 1.5% of total inorganic waste (plastic and paper). As for the TPS3R sites, only 10-20% are believed to be operational due to a lack of local and regional government funding as well as operational challenges.

In Thailand, there is a strong market structure for recycling, with multiple companies having developed formal treatment capacity and recyclers located in close proximity to the three wastesheds of Bangkok, Chon Buri and Rayong. Despite the availability of these facilities, collection of plastic waste is limited by the amount of plastics collected by the informal sector. The lack of segregation of recyclables for formal collection is also limiting market growth.

In contrast to the prevalence of formal recyclers in Thailand, wastesheds in Vietnam have a mix of both formal and informal recyclers, except for Da Nang, which does not have any known permitted plastic recyclers. The informal recyclers, in the form of craft villages4, are responsible for most of the plastics that are processed and recycled locally. However, they lack the capability to efficiently scale the quantity of plastic collected and provide consistent, high-quality feedstock flow to support investment in future infrastructure.

Enabling policies to create sustainable plastic waste management

Recognizing the limitations and challenges of existing infrastructure, and ways of working, governments play a critical role in ensuring the needed conditions and regulations are in place to strengthen plastic waste management.

One such key policy is source segregation. Local implementation of national legislation to increase source separation of recyclable material is critical to support scale-up of plastic recycling and ensure security of feedstock supply. In its absence, the amount and quality of material available for recycling remains limited to those being collected by informal waste collectors, while the majority of potential recyclables are contaminated within municipal solid waste.

Throughout all wastesheds, municipal governments have attempted to implement source segregation with various levels of success. The ‘Rayong model,’ which promotes source segregation of plastics in households and offices via a public-private partnership approach, was successfully implemented in 2018/19 and is being extended to other forms of waste generators in Thailand. However, the reported amount segregated for recycling is still very small compared to the model’s target of recycling at least 10% of plastic waste. In Hanoi, the Urban Environment Company Limited (URENCO) has implemented a small-scale program to encourage the public to segregate their recyclables; but this has yet to be rolled out across the city.

In order to drive sustained change and improvement, policy implementation has to be complemented with sufficient guidance and funding to municipal governments as well as a strong push to change household behavior to segregate recyclables.

The way forward for local plastics recycling requires a concerted effort

With an improved understanding of local ecosystem actors and existing waste management systems, initiatives and investments to scale-up plastics recycling can be more targeted and tailored to the unique needs and strengths of each wasteshed.

Nonetheless, key foundations that need to be established across all wastesheds include:

- enabling policies such as source segregation

- channeling investments to upgrade capabilities of existing infrastructure, and

- setting up the required recycling infrastructure where needed to drive local demand for plastics. This could include setting up formalized sorting infrastructure, while tapping on the strengths of informal waste pickers and collectors in the recovery of plastics recyclables.

Like the rest of the world, Asia has experienced rapid growth in plastic production and consumption over the past few decades. The scale of change needed is significant, but we have an opportunity now to turn the tide on plastic pollution through collaborative actions among governments, corporations, investors, consumers and value chain actors.

The Mapping Local Plastic Recycling Supply Chains: Insights from Selected Cities in India, Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam reports can be viewed here.

Endnotes:

1. Wastesheds are defined as a geographical region with a common solid waste disposal system, or an area designated by the governing institutions as appropriate for developing a common recycling program in each country.

2. Waste banks are semi-formal facilities managed by local communities / neighborhoods where households can deposit their waste, while acting as aggregation points for recyclables from informal collectors.

3. TPS3R sites are aggregation facilities aimed to divert recyclables from landfills.

4. Craft villages refer to villages in which many households are involved in informal waste collection, aggregation, pre-processing and even some recycling of tradable waste.